Working as a Mental Health Data Analyst within Yorkshire Ambulance Service NHS Trust, I often face the same barrier many NHS analysts do: the majority of clinical information sits locked away in free-text narratives. Whether it’s ambulance ePR notes, discharge summaries, or radiology reports, the language clinicians use is rich in meaning but extremely time-consuming to analyse manually.

I became particularly aware of this challenge and much of the information analysts were searching for such as whether pneumonia was present, or whether pleural effusion was ruled out was buried in radiology reports. The only option was to read each report individually, which was neither scalable nor reproducible.

Because of NHS information-governance restrictions, we can’t simply upload these data to an online API or large language model. All analytical work must remain on secure, often CPU-only infrastructure, behind the NHS firewall. That reality motivated me to design a lightweight, reproducible natural language processing (NLP) method in R something that analysts could run locally without GPUs or commercial AI services, yet still achieve clinically meaningful entity extraction.

The resulting workflow, prototyped using the MIMIC-IV radiology dataset, became a proof-of-concept for an approach that could, with further adaptation, be applied to NHS radiology narratives or other unstructured text sources such as ambulance ePCR notes.

Motivation: bridging the gap between manual audits and AI

In the NHS we often talk about AI, but most analysts still rely on spreadsheets and manual review. I wanted to build something that sits between those two worlds automated enough to scale, transparent enough to be trusted, and light enough to run on an NHS desktop.

The use case is clear: radiology reports describe a patient’s imaging findings in natural language. For many analytical tasks such as population-level analytics, safety monitoring, or predictive modelling we only need to know which findings were mentioned and whether they were present or absent.

Yet standard keyword searches can’t tell us that. For example, a report stating

“The lungs are clear without focal consolidation, pleural effusion or pneumothorax.”

contains the words consolidation, effusion, and pneumothorax, but all three are absent. A purely lexical match would incorrectly record them as present. Context understanding is therefore essential for accuracy.

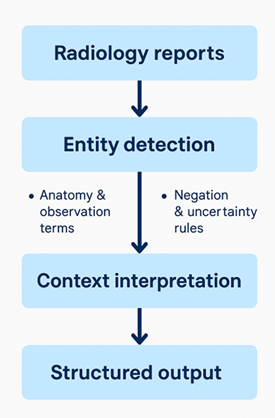

That problem distinguishing what was said from what was meant became the centrepiece of my work and as can be seen in Figure 1 below which highlights the architectural design of my pipeline.

Designing a contextual extractor

The extractor works in two stages:

- Entity detection using simple but highly tuned dictionaries of anatomical and observation terms.

- Context interpretation that determines whether each observation is present, absent, or uncertain based on nearby cue phrases.

1) Entity detection

I began by building two curated dictionaries:

- Anatomy terms – e.g., lung, pleura, mediastinum, heart, diaphragm, apex.

- Observation terms – e.g., opacity, consolidation, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, fracture, nodule, cardiomegaly.

These lists are easily extended or localised for NHS reporting styles. Each term is converted into a case-insensitive regular expression. The extractor then scans every sentence for matches and records start and end character offsets so that downstream systems can link the structured output back to the original text.

2) Context interpretation

Next, I implemented a lightweight contextual layer inspired by the ConText algorithm used in clinical NLP research. Rather than classifying with machine learning, it uses a set of linguistic rules negation, uncertainty, and termination triggers that define the scope of meaning within a sentence.

For example:

- Pre-negation triggers: “no”, “without”, “free of”, “absent”, “negative for”

- Post-negation triggers: “ruled out”, “excluded”

- Uncertainty triggers: “possible”, “likely”, “cannot exclude”, “suspicious for”

- Scope terminators: “but”, “however”, “although”

These rules are applied through regular-expression spans. Each observation term within the influence of a negation trigger is marked as absent; those under uncertainty cues are uncertain; all others default to present.

context_triggers <- list(

pre_neg = c(

"no",

"without",

"free of",

"absent",

"negative for",

"not seen",

"lack of"

),

post_neg = c("ruled out", "excluded"),

pre_uncert = c(

"possible",

"possibly",

"likely",

"cannot exclude",

"suspicious for",

"consistent with",

"in keeping with",

"questionable",

"equivocal"

),

post_uncert = c(

"may represent",

"may reflect",

"could represent",

"could reflect",

"suggesting",

"suggests",

"suggestive of",

"compatible with"

),

terminate = c("but", "however", "yet", "although", "except", "though"),

pseudo_neg = c(

"no change",

"no interval change",

"no significant change",

"no appreciable change",

"no substantial change"

)

)assign_context_certainty_sentence <- function(sent_text, ents_sentence_df) {

# detect negation/uncertainty cues and adjust certainty labels

}Extracting the right sections

To minimise false positives, the extractor first isolates only the FINDINGS and IMPRESSION sections of each report, ignoring the INDICATION text that typically contains referral questions (“rule out pneumonia”).

By focusing on the interpretive segments, the algorithm analyses the clinician’s diagnostic statements rather than their initial hypotheses.

Testing on the MIMIC-IV dataset

To validate performance, I randomly sampled 100 radiology reports from the MIMIC-IV corpus, which contains de-identified hospital data approved for research use.

Each file was read, processed, and converted into a structured tibble showing entity text, entity type, certainty, and character positions.

As seen in Table 1 below the radiology report processed through the extractor produces a structured table where every detected entity is recorded as a separate row.

| Column | Description |

|---|---|

| entity_id | Unique sequential identifier for each extracted entity. |

| doc_id | Name or ID of the source document (e.g., radiology report file). |

| sent_id | Sentence number within the document where the entity appears. |

| entity_text | Exact phrase matched from the report text (e.g., consolidation, pleural effusion). |

| entity_type | Category of the term — either Anatomy or Observation. |

| certainty | Contextual interpretation derived from nearby linguistic cues: present, absent, or uncertain. |

| start_char | Starting character position of the entity in the original text. |

| end_char | Ending character position of the entity in the original text. |

For example, the report in Table 2 below:

“No focal consolidation is seen. There is no pleural effusion or pneumothorax. The cardiac and mediastinal silhouettes are unremarkable.”

| entity_text | entity_type | certainty |

|---|---|---|

| consolidation | Observation | absent |

| pleural effusion | Observation | absent |

| pneumothorax | Observation | absent |

This confirmed the contextual logic was functioning as intended the algorithm recognised the mentions but correctly classified them as absent.

Handling complexity and edge cases

Designing a rule-based system is not without trade-offs. Radiology language can be subtle: phrases such as “cannot exclude pneumonia” or “features may represent atelectasis” require careful scope handling. I incorporated both pre- and post-modifiers to ensure flexibility, but there remain limitations around nested clauses (“no change in the previous pneumothorax”) and conditional statements (“if present, may represent infection”). These could be addressed later with dependency parsing or a hybrid model, but the goal here was to stay lightweight and interpretable something any NHS analyst could audit and understand. Another consideration was sentence boundary detection. I used the stringi package to identify sentence offsets, which preserves character indices for later reconciliation with structured EHR tables. This proved more reliable than tokenisers that lose positional information.

Performance and scalability

Because this workflow uses only base R and string-processing libraries (stringr, stringi, dplyr), it scales linearly with text length and can comfortably process tens of thousands of reports on a standard NHS laptop. There are no GPU or internet requirements, which makes it ideal for hospital-based servers where outbound connections are restricted.

While models like spaCy or transformer-based approaches such as BioBERT can achieve higher recall on complex linguistic patterns, they require substantial infrastructure and often cannot run in the secure NHS network environment. This workflow therefore fills a critical niche: interpretable, deployable, and compliant.

Integration possibilities

The structured output from this method essentially a long table of findings with certainty labels can feed into SQL databases, Power BI dashboards, or R Shiny apps. For example, analysts could summarise all radiology mentions of pneumonia marked as “present” across an entire hospital trust, or measure how often “pleural effusion” was reported in specific cohorts. The same pattern could also be adapted to ambulance ePCR narratives, mental-health crisis notes, or pathology reports.

Code availability

Full code is publicly available in my GitHub account.