greet_person <- function(greeting = "Hello World", sender = "the NHS-R Community!") {

if (!is.character(greeting)) {

stop("greeting must be a string")

}

if (!is.character(sender)) {

stop("sender must be a string")

}

if (length(sender) > 1) {

warning("greet_person isn't very good at handling more than one sender. It is better to use just one sender at a time.")

}

message(greeting, " from ", sender)

}At the NHS R Conference, I suggested to people that they should embrace the idea of package-based development rather than script-based work.

In the first part of this tutorial, in the fictional NHS-R Community greeting room, our humble analyst was tasked with greeting people. Rather than writing a script and needing to repeat themselves all the time with different variations of greetings and senders, they wrote a rather nifty little function to do this:

As we know, R is awesome and many people took up R on the background of some excellent publicity and training work by the NHS-R community. Our poor greeting team got overwhelmed by work: it is decided that the team of greeters needs to expand. There will now be a team of three greeters. Every other bit of work output from our NHS-R community team will involve greeting someone before we present our other awesome analysis to them.

This is going to be a nightmare! How can we scale our work to cope with multiple users, and multiple other pieces of work using our greeting function.

If we rely upon the scripts, we have to trust that others will use the scripts appropriately and not edit or alter them (accidentally or on purpose). Furthermore, if someone wants to greet someone at the beginning of their piece of analysis, they’ll either have to copy the code and paste it somewhere, or link to our script containing the function – which in turn means they need to keep a common pathname for everything and hope no-one breaks the function. Nightmare!

Fortunately, someone attended the last NHS-R conference and remembered that package-based development is a really handy way of managing to scale your R code in a sustainable way. So after a team meeting with copious caffeine, it is decided that greet_person needs to go into a new package, cunningly named {NHSRGreetings}. And here’s how we’re going to do it.

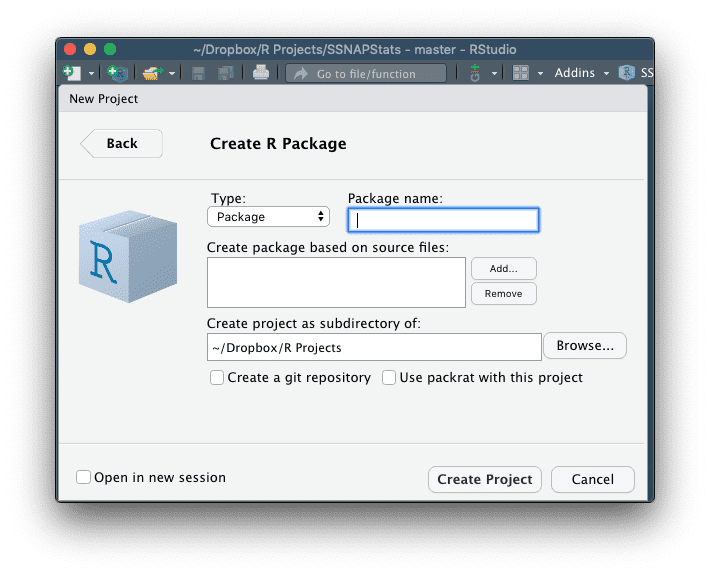

In R Studio, go to File and then to New Project. Click on New Directory, and then click on R Package. I am using RStudio 1.2 Preview for this tutorial which is downloadable from the R website. I would recommend doing this as some of the package management has been greatly simplified and some frustrating steps removed.

Click on ‘Open in new session’ (so we can see the original code), and set the Package name as {NHSRGreetings}. We could just pull our old source files into the package – but for this tutorial I’m going to do things the longer way so you also know how to create new functions within an existing package.

Set the project directory to somewhere memorable.

For now don’t worry about the git or {packrat} options – those are tutorials within themselves!

You are greeted with a package more or less configured up for you. A single source file, hello.R is set up for you within an R directory within the package. It’s not as cool as our function of course, but it’s not bad! It comes with some very helpful commented text:

# Hello, world!

#

# This is an example function named 'hello'

# which prints 'Hello, world!'.

#

# You can learn more about package authoring with RStudio at:

#

# http://r-pkgs.had.co.nz/

#

# Some useful keyboard shortcuts for package authoring:

#

# Install Package: 'Cmd + Shift + B'

# Check Package: 'Cmd + Shift + E'

# Test Package: 'Cmd + Shift + T'So let’s check if the comments are right – hit Cmd + Shift + B on a Mac (on Windows and Linux you should see slightly different shortcuts). You can also access these options from the Build menu in the top right pane.

You will see the package build. R will then be restarted, and you’ll see it immediately performs the command library(NHSRGreetings) performed, which loads our newly built package.

If you type hello() at the command line, it will do as you may expect it to do!

So – time to customise our blank canvas and introduce our much more refined greeter.

In the root of our project you will see a file called DESCRIPTION. This contains all the information we need to customise our R project. Let’s customise the Title, Author, Maintainer and Descriptions for the package.

We can now create a new R file, and save it in the R subdirectory as greet_person.R. Copy over our greet_person function. We should be able to run install and our new function will be built in as part of the package.

We can now get individual team members to open the package, run the build once on their machine, and the package will be installed onto their machine. When they want to use any of the functions, they simply use the command library(NHSRGreetings) and the package will be ready to go with all the functions available to them. When you change the package, the authors will have to rebuild the package just the once to get access to the new features.

When writing packages it is useful to be very wary about namespaces. One of the nice things about R is that there are thousands of packages available. The downside is that it makes it very likely that two individuals can choose the same name for a function. This makes it doubly important to pick appropriate names for things within a package.

For example, what if instead of the NHS-R Community package someone wrote a {CheeseLoversRCommunity} package with a similarly names greet_person, but it did something totally different?

In a script, you have full control over the order you load your packages, so R will happily let you call functions from packages and trust that you know what order you loaded things in.

If you are a package author however, it’s assumed you may be installed on many machines, each with a potentially infinite set of combinations of different packages with names that may clash (or if they don’t already they might do in the future).

So within the package, any function which doesn’t come from R itself needs to have clearly defined which package it has come from.

Within DESCRIPTION you must define which package you use, and the minimum version. You do this with the Imports keyword. Attached is the Imports section of one of the SSNAP packages:

Imports:

methods (>= 3.4.0),

lubridate (>= 1.7.4),

tibble (>= 1.4.2),

dplyr (>= 0.7.5),

tibbletime (>= 0.1.1),

glue (>= 1.2.0),

purrr (>= 0.2.5),

rlang (>= 0.2.0),

readr (>= 1.1.1),

stringr (>= 1.3.1),

ssnapinterface (>= 0.0.1)Next within your functions, rather than just calling the functions use the package name next to the function. For example instead of calling mutate() from the {dplyr} package, refer to it as dplyr::mutate() which tells R you mean the mutate function from the {dplyr} package rather than potentially any other package. There are ways to declare functions you are using a lot within an individual file – but this method makes things pretty foolproof.

Another tip is to avoid the {magrittr} pipe within package functions. Whilst {magrittr} makes analysis scripts nice and clean, firstly you still have the namespace issue to deal with (%>%).

Is actually a function, just one with a funny name – it is really called magrittr::%>%() !) Secondly the way {magrittr} works can make debugging difficult. You don’t tend to see that from a script. But if you’re writing code in a package, which calls a function in another package, which calls code in another package, which uses {magrittr} – you end up with a really horrid nest of debugging errors: it is better to specify each step with a single variable which is reused.

When you’ve got your code in, the next important thing to do is check your package. Build simply makes sure your code works. Check makes sure that you follow a lot of ‘rules’ of package making – including making sure R can safely and clearly know where every R function has come from. Check also demands that all R functions are documented: something which is outside of the scope of this tutorial and is probably the subject for another blog post – a documented function means if you type ?greet_person that you should be able to see how to use the function appropriately. It can help you create your own website for your package using the pkgdown package.

If your package both builds and checks completely and without errors or warnings, you might want to think about allowing the wider public to use your project. To do this, you should consider submitting your project to CRAN. This involves a fairly rigorous checking process but means anyone can download and use your package.

If we can get enough people to develop, share their code and upload their packages to CRAN we can work together to improve the use of R across our community.

Feedback and responses to @drewhill79.

This blog was written by Dr. Andrew Hill, Clinical Lead for Stroke at St Helens and Knowsley Teaching Hospitals.

Back to top