When I started my job at The Strategy Unit, the first task I was given was:

Can you build some QA processes for our model?

My team develops and maintains a large, open source statistical model used to estimate how big hospitals of the future should be. The code was well structured, documentated and tested, but hardly anyone had thought about QA formally.

I’d worked with ISO 9001 before, but I’d never tried to design QA for a statistical model. So I went on a journey trying to figure out what processes we needed, and how we could integrate QA into the way the team was already working.

What do I mean by QA?

Quality work is about how we build models. Choosing appropriate methods, writing clean code and making sure everything is reproducible.

Quality assurance, on the other hand, is about building trust. It ensures the right processes are followed, results are checked, and outputs are credible and interpretable.

Why does QA matter?

Public organisations often rely heavily on models to make decisions. If a model has errors, unrealistic assumptions, or poor documentation, it can result in wasted resources, bad decisions and loss of public confidence.

The National Audit Office (NAO) found1 that common problems include:

- Poor data or unrealistic assumptions

- No uncertainty or sensitivity testing

- Weak documentation and governance

Our model influences hospital planning across the NHS, so it’s vital that people can trust it.

What was missing?

Quality assurance effort should be appropriate to the risk associated with the intended use of the analysis

To find the missing pieces, I turned to existing guidance across governement and auditing organisations:

- Framework to review models, NAO

- HM Treasury’s AQuA book

- Quality assurance of models: a guide for audit committees, NAO

- The Department for Energy Security & Net Zero (DESNZ) and Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Modelling Quality Assurance tools and guidance

- Duck book

Turns out, we were already doing a lot of what they recommend:

| QA Component | Already Have? | How |

|---|---|---|

| Change log | ✅ | GitHub |

| Technical guide | ✅ | Code documentation |

| User guide | ✅ | Quarto website |

| Roles/responsibilities | ✅ | Quarto website |

| Assumptions log | ✅ | Quarto website |

| QA plan | ❌ | - |

| QA log | ❌ | - |

All our code was version-controlled, so we already had a change log. We maintained a Quarto website with user guidance, and wrote documentation alongside the code, which served as our technical guide.

The main pieces missing were a QA plan and a QA log.

Not another spreadsheet

A QA plan is simply a list of the tasks you intend to do to improve the quality of your model.

A QA log is a record of what you’ve already done, who did it, and when they did it.

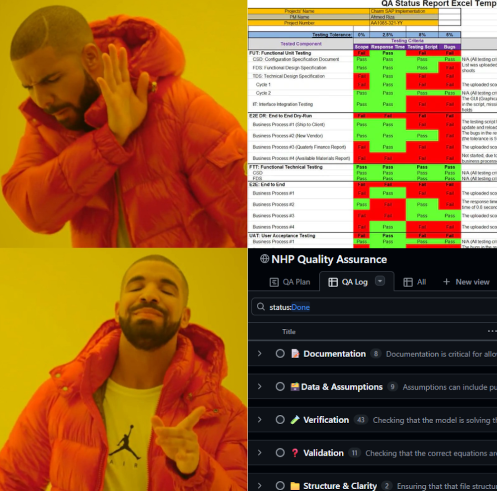

I scoured the internet looking for examples from other organisations. Almost everything I found was in spreadsheets.

The most comprehensive example I came across was from the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) in their Quality Assurance (QA) tools and guidance.

However, the templates were mostly designed for Excel-based models and still just big, colour-coded spr.jpgeadsheets.

My heart sank at the thought of having to manage QA with an ugly spreadsheet. There had to be a better way.

GitHub to the rescue

Our team was already using Git and GitHub for the model code and had just started experimenting with using GitHub projects for planning.

So I thought: what if we used a GitHub project for our QA plan and log too?

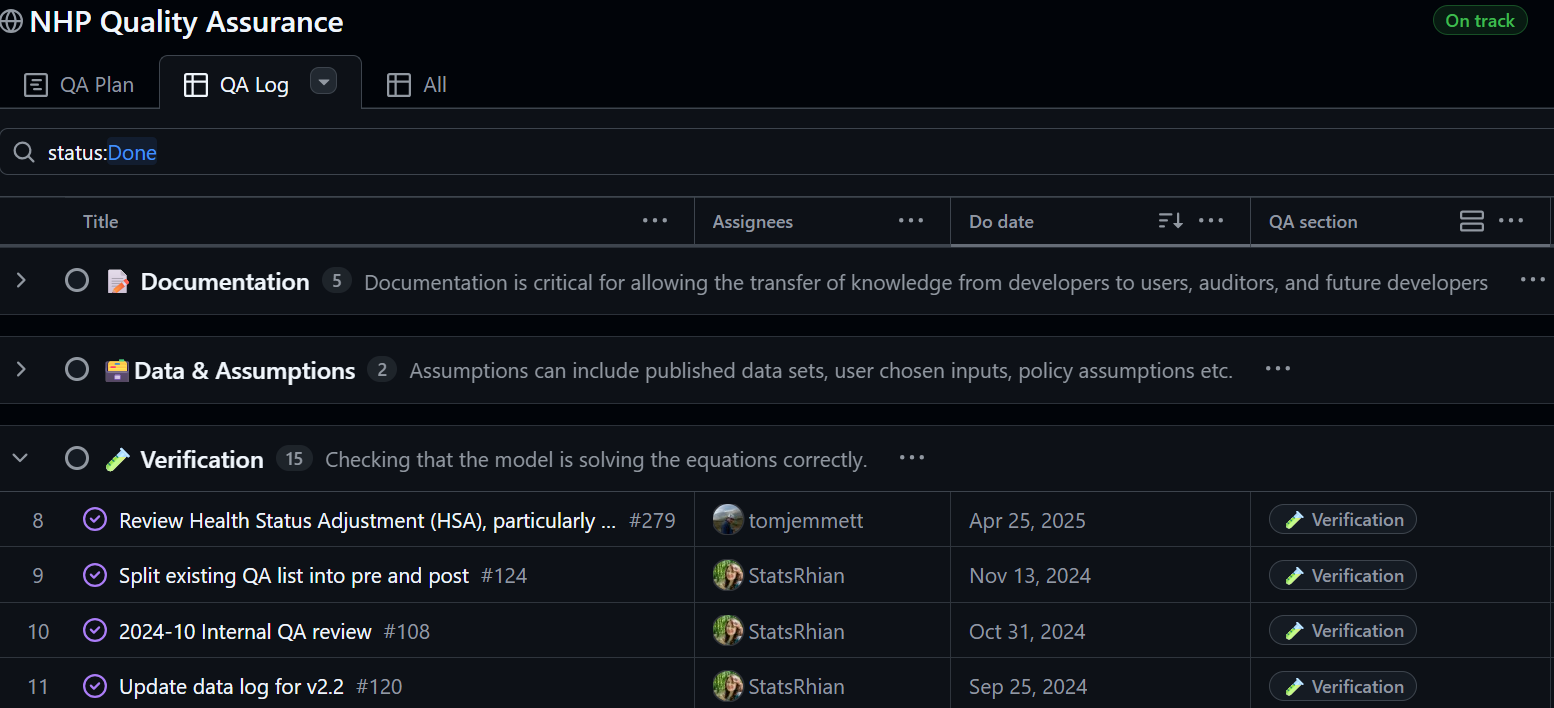

I set up a new GitHub project with two views:

- Open issues ➡️ QA plan

- Complete issues ➡️ QA log

Then I browsed our repositories and added any quality assurance related issues to the board.

Our model spans multiple repos, mostly public, but some private. The project board handles this seamlessly, showing public issues to everyone and private ones only to those with access.

I also decided to add labels to the QA issues, based on the QA type.

- 📝 Documentation

- 🗃️ Data & Assumptions

- 🧪 Verification

- ❓Validation

- 📁 Structure & Clarity

People2 often get verification and validation muddled up. Verification checks that the model solves the equations correctly. Validation is checks that it’s solving the right equations.

QA in practice

Now, whenever I’m working on something QA related, I simply add it to the project board.

When we prepare our monthly model releases, we use a GitHub issue template work through a release QA checklist.

Every six months, I also do an internal QA review using another issue template.

Remove the friction

This works because QA happens where the work happens. Our developers already live in GitHub. Asking them to open a spreadsheet every time they make a model improvement just doesn’t fit how our team works. But asking them to add metadata to an issue they’re already working on, does.

Instead of a static row in an abandoned spreadsheet, each QA item has its own discussion thread, links to relevant code or analysis, and version history.

QA as a habit, not a chore

Creating and maintaining a strong culture of quality assurance is vital for ensuring analysis is robust and of a high quality. The AQuA book.

QA isn’t about ticking boxes. It’s about building trust.

There’s still plenty more to do, but moving our QA plan into GitHub has made QA part of daily coding, not an extra task at the end.

If you’ve found other ways of managing QA (without the colour-coded spreadsheets!), I’d love to hear from you.

Footnotes

myself included↩︎